June 15, 2005

BBC: The kinship of strangers

By Rob Liddle

BBC News website

What do family historians do when the trails for their own kin go cold? They join forces to uncover the life history of a randomly chosen individual from the past.

Pursuing one's ancestry used to be a labour-intensive affair - all packed lunches, trips to dusty records offices and unseemly fights over tomes with other frazzled researchers.

One would often return home empty-handed, no closer to solving the mystery of the missing cousins, where all the money went or why no-one ever talked about Uncle Bill.

Now, with a wealth of genealogical information available online and an explosion in the number of people eager to research their roots, family history can be a completely different experience.

You can access birth, marriage and death indexes and census details instantaneously and quickly link up with people who have other useful resources at their disposal or specialist knowledge.

Random number

And with these developments a new breed of genealogist has emerged - ready to root at will and for whom the process of recreating people's lives and times is an end in itself.

Members of the 16,000-strong Rootschat forum now take part in a monthly challenge, in which an individual with whom none of them has any known connection is randomly selected from the 1881 census.

The job is to find out as much as possible about the mystery person within the next four weeks. It's pot luck - the person could have died a week later - but there's always something interesting to discover about them.

"I suppose it's almost like getting a bit of a hit," explains Sarah Mackay, who with partner Trystan Davies set up Rootschat, which attracts up to 140 new members every day.

"People doing their own family may get stuck for years, but it's very addictive and when you can't get any further yourself, you're still quite desperate for the same hit.

"Which is when they start casting further afield into someone else's family group.

Killed in war

"It's almost like it becomes your own family. What I can't get over is the amount of detail people will go into."

Randomly chosen Abraham Bland, of Sale, Cheshire, started off as simply a name in the 1881 census, but a month later he was the subject of hundreds of postings, some including photographs.

The son of a landscape gardener and strict Sabbatarian - who wouldn't allow meals to be cooked on Sundays - the 5ft 7in-tall blue-eyed blond (chest measurement 34in), known as Len, emigrated to Canada in 1904, set up his own six-acre homestead and kept cattle.

He joined the armed forces in 1916 and went with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces to England, where he was based at Sandling Camp in Kent, and then to France, where he was killed in the battle of Vimy Ridge on 22 August 1917. He left no wife or children.

Censuswhacking

There is a serious side to the project, and the hope is that the randomly chosen person will fit into another researcher's family tree - something which has actually happened on each occasion so far.

Researcher Paul Etherington, who initiated the challenges, sees the site as a "truly altruistic experience".

"My own experience was that I was given advice and guidance by total strangers, and it only made me determined to want to offer the same to others.

"There's a definite pleasure to be had in helping others to find their way through to their ancestors. It must be the same kick that teachers get when a pupil suddenly gets a point they're trying to put across."

Paul also came up with the idea of censuswhacking - searching for a first name, surname or occupation that appears only once in a given census (as transcribed) - which has proved a big hit on the site.

Where else would the lives of Ginnie Pig, Spud Murphey and Alfred Goold - 1901 occupation "living on condensed milk" - be recorded for posterity?

CENSUSWHACKS

- Fatty Atkinson, 1881

- Peter Pan, 1891

- Banana Pointer, 1891

- Crusoe Robinson, 1871

- Clara Slime, 1901

- Nasty Clough, 1861

- Ester Bunney, 1871

- Sherwood Forest, 1901

June 02, 2005

Why Crush the Moon?

By Wil McCarthy

Ever since Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's 1943 children's novel, The Little Prince, science-fiction writers have dreamed of tiny planets -- planettes, if you will -- wrapped in tiny atmospheres and clothed in plants and cottages, animals and people. Few writers have concerned themselves, though, with the formidable technical details. The first and largest problem is also the most obvious: gravity. Large bodies like the Earth have got a lot of it, while small bodies like asteroids and moons have only a little. On a mile-wide sphere of rock, there's only the faintest tug of attraction; the air and houses and people would simply drift away into outer space. But science offers us an interesting trick here, because a celestial body's surface gravity depends not only on its mass but also on its radius. To put it very simply: a small, dense object puts you closer to the center than a large, fluffy object of equal mass. Hence, gravity's pull is greater.

With a superdense core surrounded by an outer husk of ordinary rock and dirt, it should be possible to build Earthlike gravity into objects just a few meters across. But here you run into two additional problems: tidal forces and escape velocity. "Tide" is basically a word for variations in gravity, and on a small, dense planet these would be very strong. A world the size of a Volkswagen, for example, might pull your feet with one full Earth gravity (1 g or "one gee" in the language of physics), but your head would feel only one-fourth as much! Think of the dizziness, the health problems, the general inconvenience.

The other problem is more serious, because it results in suffocation. "Escape velocity" is the speed an object has to be moving to break free of a gravity well and sail off into interplanetary space. Here on Earth's surface, this speed is a comfortable 11.9 kilometers per second -- enough to keep us all firmly in place, and to make it really expensive to send probes and spaceships off to other planets. On a smaller body like the moon, escape velocity is only 2.4 km/sec, which is why the moon has no atmosphere. See, air molecules are never motionless; even in a closed room, they bounce around at high speed, colliding with the walls and with each other. At room temperature and sea-level pressure, the average velocity of an oxygen molecule is around 450 meters per second. Unfortunately, the maximum velocity can be much higher -- several kilometers per second -- which is fast enough to escape the moon's gravity, slowly bleeding the atmosphere away.

On our VW-sized planette the situation is even worse, because escape velocity is only 6 meters per second -- running speed -- which means neither you nor the air will be hanging around for long. Of course, the problems of tidal stress and escape velocity can both be reduced by making the planette larger; with a diameter of 500 meters it'd have a tidal gradient only 20 percent as steep, and would be capable of hanging onto air molecules moving 40 m/sec. This is a definite improvement, although still not enough to make the place livable. A denser atmosphere weighed down by heavy molecules would also help, but you'd still need some technology for cooling off the upper atmosphere, slowing down those gas molecules, and unfortunately if the power ever failed, so would the air. Make no mistake: While planettes of this kind are physically possible, they won't persist forever without stewardship. In this sense, they're more like space stations than planets.

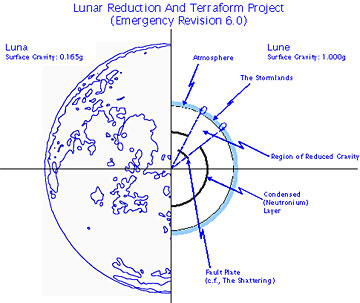

But here we can combine the best of both worlds (or both types of worlds) by taking a large, airless body like the moon and compressing it. Reducing the moon's diameter by 60 percent (from 3,476 to 1,414 kilometers), we bring its outside closer to its center, increasing its surface gravity from 0.165 to 1.000 g -- a perfect match for Earth. Better still, this increases the escape velocity from 2.4 to 3.72 km/sec, which is more than enough to hold onto an oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere. Tidal gradients would be negligible, and best of all, this "Earthlike" planette would be three times easier to escape from than the Earth itself. That is, a rocketship would need only one-third as much velocity -- or one-ninth as much energy! -- to get away. Such huge savings, combined with the safety and convenience of a real atmosphere, would make the squozen moon a perfect spaceport -- indeed, the main hub for all interplanetary traffic. Pretty cool, eh?

A matter of gravity

The dimensions of this remodeled satellite give it a surface area of 6.28 million square kilometers -- about 17 percent of its original area, or 1.7 percent of Earth's. This is roughly the size of China or India, so it's no great stretch to imagine hundreds of millions of people living there in perfect comfort and happiness. Because angular momentum is always conserved, reducing the diameter of the moon also shrinks its rotation period by a factor of 6. As a result, the moon's current solar day of 29.53 Earth days (708.72 hours) would be shortened to a more palatable 4.92 days (118.12 hours). For convenience, we might adjust that to exactly 5 Earth days, or 120 hours, and if we want to spend the extra energy, we could even strap nuclear rockets around the equator to spin it faster. A 24-hour day, anyone?

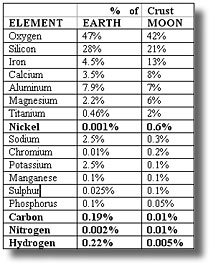

Of course, having the right gravity and rotation period does not, by itself, make a habitable world. After all, Venus has almost exactly the same gravity as Earth, while Mars has almost exactly the same spin, and neither one is exactly homey. They don't have any free oxygen in their atmospheres, and both have too much carbon dioxide. Venus has too much sulfur, too, making it highly acidic as well as hot. In some ways the moon is actually a bit more friendly, being very similar to Earth in all but four basic elements. Here's a quick comparison of soil chemistry:

Since we can extract oxygen right out of SiO2 in the rocks, the only real problems are a lack of carbon and hydrogen in the lunar soil and an overabundance of toxic nickel. The figures on nitrogen are misleading, since Earth's atmosphere contains a huge reservoir of this element, whereas the moon does not. A dense nitrogen atmosphere is certainly necessary to support Earthly life, so one would need to be imported. This could require a really large number of tanker ships, but if technology weren't a limiting factor, I'd personally vote for quantum teleportation, to pull down nitrogen and methane from Titan (Saturn's largest moon). The same technology could extract water from Europa (one of Jupiter's frozen children), to flood the landscape with small oceans that would stabilize the climate, create wildlife habitats, and provide a limitless reservoir of drinking water for the squozen moon's residents.

Sprucing up a satellite

Of course, after all this crushing and dumping and mixing, the air and water will be filled with all sorts of strange contaminants, and we'll have no easy way of cleaning or renewing them unless we install a working ecology. This process is called "terraforming," and has been a mainstay of science fiction ever since Olaf Stapledon's novel First and Last Men in 1930 (though the term itself was coined in 1949 by Jack Williamson). If you're reading this column, I can only assume you know the basics: first you import microbes, then engineered lichens and plants, then animals and, finally, humans. So many descriptions of this process were written over the span of the 20th century that I have very little to add here, except to say that the shock troops -- the first microbes into a hostile environment -- had better be rugged little critters.

Many biologists speculate that the ultimate temperature limit for single-celled "life as we know it" (i.e., life that's compatible with ours) may be as high as 160 degrees Centigrade, while the lower limit (as observed in Antarctica) seems to be around -12 degrees Centigrade. Many bacteria, and their primitive cousins the archaea, can survive long exposure to vacuum, which is certainly helpful in any terraforming operation. The same organisms can often survive at pressures as high as 300 atmospheres (i.e., 300 times the pressure of Earth's atmosphere), and "barophilic" or pressure-loving bacteria can thrive at up to 500 atmospheres. Nothing we know of can live without water, and because salt allows water to conduct electricity, life needs that as well. It can get by, though, with very dilute solutions like pond water, whereas extremely salty solutions will dehydrate most living things. The upper limit for salt tolerance seems to be around 33 percent solution, which is quite a lot if you consider that Earth's oceans -- which can kill land and freshwater life -- are only at 3 percent. Similarly, most organisms can't stand large variations in acidity, because acids and bases are both highly corrosive. Most life exists in a range of pH from around 5 to 8 (mildly acidic to mildly basic). However, there are bacteria capable of surviving in pH less than 1 -- acidic enough to dissolve metal! -- and as high as 11.5, which is equivalent to a weak solution of lye and can literally convert most cell membranes into soap.

Engineering a single organism to survive all these extremes is likely impossible, but we'd want to come as close as we could. We'd also want something that could produce oxygen, not only by photosynthesis but also through other chemical reactions, fueled by the very pollutants we want to remove from the crushed moon's air and water. And to cope with a rapidly changing environment, they should also be capable of surviving long periods of drought and starvation. And yet, we need our superorganisms to be either very friendly to human life, or else very, very easy to kill when they've outlived their usefulness. Otherwise, we might find we've gone to all this trouble to prepare a world not for ourselves, but for them.

We all love the large, pale moon that hangs in our nighttime sky. A half-sized blue and green one will definitely take some getting used to, especially when its dark side starts lighting up with cities. Still, the prospect of a new world -- large enough to house the entire United States, accessible enough to serve as the airline hub for an entire solar system, and yet safe enough to survive a technological collapse -- may be too good to pass up. Besides, who wants to live in the same old house for all eternity? Sooner or later, you've got to remodel.

Sources used for writing are:

McCarthy, Wil: To Crush the Moon (Appendix C: Technical Notes), Bantam Books, June 2005

Wikipedia: ("Terraforming"): http://www.wikipedia.org

McCarthy, Wil: Hacking Matter, Basic Books, 2004

Postgate, John: The Outer Reaches of Life, Cambridge University Press, 1994

Roger Bate, Donald D. Mueller and Jerry E. White: Fundamentals of Astrodynamics, Dover Publications, Inc., 1971

The Encyclopedia Britannica, 2004 Edition ("Moon")

Gillett, Stephen L.: World-Building, Writer's Digest Books, 1996

Wil McCarthy is a rocket guidance engineer, robot designer, nanotechnologist, science-fiction author and occasional aquanaut. He has contributed to three interplanetary spacecraft, five communication and weather satellites, a line of landmine-clearing robots and some other "really cool stuff" he can't tell us about. His short writings have graced the pages of Analog, Asimov's, Wired, Nature and other major publications, and his book-length works include the New York Times notable Bloom, Amazon "Best of Y2K" The Collapsium and, debuting this month, To Crush the Moon. His acclaimed nonfiction book, Hacking Matter, is now available in paperback.

NYTimes: Creating Language

May 31, 2005

Devoid of Content

By STANLEY FISH

Chicago

WE are at that time of year when millions of American college and high school students will stride across the stage, take diploma in hand and set out to the wider world, most of them utterly unable to write a clear and coherent English sentence. How is this possible? The answer is simple and even obvious: Students can't write clean English sentences because they are not being taught what sentences are.

Most composition courses that American students take today emphasize content rather than form, on the theory that if you chew over big ideas long enough, the ability to write about them will (mysteriously) follow. The theory is wrong. Content is a lure and a delusion, and it should be banished from the classroom. Form is the way.

On the first day of my freshman writing class I give the students this assignment: You will be divided into groups and by the end of the semester each group will be expected to have created its own language, complete with a syntax, a lexicon, a text, rules for translating the text and strategies for teaching your language to fellow students. The language you create cannot be English or a slightly coded version of English, but it must be capable of indicating the distinctions - between tense, number, manner, mood, agency and the like - that English enables us to make.

You can imagine the reaction of students who think that "syntax" is something cigarette smokers pay, guess that "lexicon" is the name of a rebel tribe inhabiting a galaxy far away, and haven't the slightest idea of what words like "tense," "manner" and "mood" mean. They think I'm crazy. Yet 14 weeks later - and this happens every time - each group has produced a language of incredible sophistication and precision.

How is this near miracle accomplished? The short answer is that over the semester the students come to understand a single proposition: A sentence is a structure of logical relationships. In its bare form, this proposition is hardly edifying, which is why I immediately supplement it with a simple exercise. "Here," I say, "are five words randomly chosen; turn them into a sentence." (The first time I did this the words were coffee, should, book, garbage and quickly.) In no time at all I am presented with 20 sentences, all perfectly coherent and all quite different. Then comes the hard part. "What is it," I ask, "that you did? What did it take to turn a random list of words into a sentence?" A lot of fumbling and stumbling and false starts follow, but finally someone says, "I put the words into a relationship with one another."

Once the notion of relationship is on the table, the next question almost asks itself: what exactly are the relationships? And working with the sentences they have created the students quickly realize two things: first, that the possible relationships form a limited set; and second, that it all comes down to an interaction of some kind between actors, the actions they perform and the objects of those actions.

The next step (and this one takes weeks) is to explore the devices by which English indicates and distinguishes between the various components of these interactions. If in every sentence someone is doing something to someone or something else, how does English allow you to tell who is the doer and whom (or what) is the doee; and how do you know whether there is one doer or many; and what tells you that the doer is doing what he or she does in this way and at this time rather than another?

Notice that these are not questions about how a particular sentence works, but questions about how any sentence works, and the answers will point to something very general and abstract. They will point, in fact, to the forms that, while they are themselves without content, are necessary to the conveying of any content whatsoever, at least in English.

Once the students tumble to this point, they are more than halfway to understanding the semester-long task: they can now construct a language whose forms do the same work English does, but do it differently.

In English, for example, most plurals are formed by adding an "s" to nouns. Is that the only way to indicate the difference between singular and plural? Obviously not. But the language you create, I tell them, must have some regular and abstract way of conveying that distinction; and so it is with all the other distinctions - between time, manner, spatial relationships, relationships of hierarchy and subordination, relationships of equivalence and difference - languages permit you to signal.

In the languages my students devise, the requisite distinctions are signaled by any number of formal devices - word order, word endings, prefixes, suffixes, numbers, brackets, fonts, colors, you name it. Exactly how they do it is not the point; the point is that they know what it is they are trying to do; the moment they know that, they have succeeded, even if much of the detailed work remains to be done.

AT this stage last semester, the representative of one group asked me, "Is it all right if we use the same root form for adjectives and adverbs, but distinguish between them by their order in the sentence?" I could barely disguise my elation. If they could formulate a question like that one, they had already learned the lesson I was trying to teach them.

In the course of learning that lesson, the students will naturally and effortlessly conform to the restriction I announce on the first day: "We don't do content in this class. By that I mean we are not interested in ideas - yours, mine or anyone else's. We don't have an anthology of readings. We don't discuss current events. We don't exchange views on hot-button issues. We don't tell each other what we think about anything - except about how prepositions or participles or relative pronouns function." The reason we don't do any of these things is that once ideas or themes are allowed in, the focus is shifted from the forms that make the organization of content possible to this or that piece of content, usually some recycled set of pros and cons about abortion, assisted suicide, affirmative action, welfare reform, the death penalty, free speech and so forth. At that moment, the task of understanding and mastering linguistic forms will have been replaced by the dubious pleasure of reproducing the well-worn and terminally dull arguments one hears or sees on every radio and TV talk show.

Students who take so-called courses in writing where such topics are the staples of discussion may believe, as their instructors surely do, that they are learning how to marshal arguments in ways that will improve their compositional skills. In fact, they will be learning nothing they couldn't have learned better by sitting around in a dorm room or a coffee shop. They will certainly not be learning anything about how language works; and without a knowledge of how language works they will be unable either to spot the formal breakdown of someone else's language or to prevent the formal breakdown of their own.

In my classes, the temptation of content is felt only fleetingly; for as soon as students bend to the task of understanding the structure of language - a task with a content deeper than any they have been asked to forgo - they become completely absorbed in it and spontaneously enact the discipline I have imposed. And when there is the occasional and inevitable lapse, and some student voices his or her "opinion" about something, I don't have to do anything; for immediately some other student will turn and say, "No, that's content." When that happens, I experience pure pedagogical bliss.

Stanley Fish is dean emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

June 01, 2005

Joseph E. Michael Jr.

1923 - 2005

DURHAM -- After a period of failing health, Joseph E. Michael, Jr., died May 26, 2005 at Exeter Hospital. He was a resident of Durham for more than 50 years.

Born at Dover Hospital on October 1, 1923, he was the son of Antoinette and Joseph Michael. He was the youngest of nine children and resided in Rochester, N.H. He graduated from Rochester High School and was proud to have earned the honor of Eagle Scout. He entered Dartmouth College with the Class of 1945, but his studies were interrupted by military service in the Army Air Corps. After returning to New Hampshire, he resumed his college career, graduating from Dartmouth and the Boston University School of Law in 1950.

He married in 1949 and began practicing law in Rochester. He was later appointed District Court Judge of Durham, and most recently had been Of Counsel in the law firm of Swanson and Hand in Newmarket, N.H. A member of the New Hampshire Bar Association, Judge Michael was licensed to practice in Federal Court. He also served as a Director of the First National Bank of Rochester and as a Director and General Counsel for the Profile Bank FSB.

He taught undergraduate and graduate law courses at the University of New Hampshire for more than four decades. Among other duties, he served as Durham Town Moderator for many years, helping to guide the town when the proposed Onassis Oil Refinery threatened New Hampshire's seacoast. A founding member of St. George's Episcopal Church in Durham, and an active church member for more than 50 years, he was a Trustee of the Diocease of New Hampshire and a delegate to many state and national conventions. Additionally, he was a Trustee of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States' Pension Fund for many years.

He is survived by his wife, Shirley Whiting Michael; his daughter, Christine Nevada Michael; his son, Joseph E. Michael III; his daughter-in-law, Susan Lavallee; his son-in-law, Martin White; and five grandchildren-Aditep, Carmen, Isabel, and Jonathan White, and Cameron Michael; his brother, George Michael; and many beloved nieces, nephews, in-laws, and cousins.

His life was enriched by his love of the outdoors. He delighted in his hours on the water: at his cottage on Crystal Lake; during his annual fishing trip to Moosehead Lake in Maine; while boating on Little Bay; and when sailing the Eastern Atlantic Coast. He was a ticket holder and an avid enthusiast of all sports at the University of New Hampshire, and he spent many summers coaching Little League baseball in Durham. He enjoyed travel in the United States and in Europe, but his most treasured moments were spent with his family and close friends.

A private service will be held for family members. A public memorial service will be held in July; details will be forthcoming.

In lieu of flowers, a contribution can be made to the Joseph Michael Memorial Fund of the Gilmanton Land Trust. The address is P.O. Box 561, Gilmanton, New Hampshire, 03237, and contributions should be marked "Attention Nanci Mitchell."

NYTimes: C.I.A. Expanding Terror Battle Under Guise of Charter Flights

This article was reported by Scott Shane, Stephen Grey and Margot Williams and written by Mr. Shane.

SMITHFIELD, N.C. - The airplanes of Aero Contractors Ltd. take off from Johnston County Airport here, then disappear over the scrub pines and fields of tobacco and sweet potatoes. Nothing about the sleepy Southern setting hints of foreign intrigue. Nothing gives away the fact that Aero's pilots are the discreet bus drivers of the battle against terrorism, routinely sent on secret missions to Baghdad, Cairo, Tashkent and Kabul.

When the Central Intelligence Agency wants to grab a suspected member of Al Qaeda overseas and deliver him to interrogators in another country, an Aero Contractors plane often does the job. If agency experts need to fly overseas in a hurry after the capture of a prized prisoner, a plane will depart Johnston County and stop at Dulles Airport outside Washington to pick up the C.I.A. team on the way.

Aero Contractors' planes dropped C.I.A. paramilitary officers into Afghanistan in 2001; carried an American team to Karachi, Pakistan, right after the United States Consulate there was bombed in 2002; and flew from Libya to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the day before an American-held prisoner said he was questioned by Libyan intelligence agents last year, according to flight data and other records.

While posing as a private charter outfit - "aircraft rental with pilot" is the listing in Dun and Bradstreet - Aero Contractors is in fact a major domestic hub of the Central Intelligence Agency's secret air service. The company was founded in 1979 by a legendary C.I.A. officer and chief pilot for Air America, the agency's Vietnam-era air company, and it appears to be controlled by the agency, according to former employees.

Behind a surprisingly thin cover of rural hideaways, front companies and shell corporations that share officers who appear to exist only on paper, the C.I.A. has rapidly expanded its air operations since 2001 as it has pursued and questioned terrorism suspects around the world.

An analysis of thousands of flight records, aircraft registrations and corporate documents, as well as interviews with former C.I.A. officers and pilots, show that the agency owns at least 26 planes, 10 of them purchased since 2001. The agency has concealed its ownership behind a web of seven shell corporations that appear to have no employees and no function apart from owning the aircraft.

The planes, regularly supplemented by private charters, are operated by real companies controlled by or tied to the agency, including Aero Contractors and two Florida companies, Pegasus Technologies and Tepper Aviation.

The civilian planes can go places American military craft would not be welcome. They sometimes allow the agency to circumvent reporting requirements most countries impose on flights operated by other governments. But the cover can fail, as when two Austrian fighter jets were scrambled on Jan. 21, 2003, to intercept a C.I.A. Hercules transport plane, equipped with military communications, on its way from Germany to Azerbaijan.

"When the C.I.A. is given a task, it's usually because national policy makers don't want 'U.S. government' written all over it," said Jim Glerum, a retired C.I.A. officer who spent 18 years with the agency's Air America but says he has no knowledge of current operations. "If you're flying an executive jet into somewhere where there are plenty of executive jets, you can look like any other company."

Some of the C.I.A. planes have been used for carrying out renditions, the legal term for the agency's practice of seizing terrorism suspects in one foreign country and delivering them to be detained in another, including countries that routinely engage in torture. The resulting controversy has breached the secrecy of the agency's flights in the last two years, as plane-spotting hobbyists, activists and journalists in a dozen countries have tracked the mysterious planes' movements.

Inquiries From Abroad

The authorities in Italy and Sweden have opened investigations into the C.I.A.'s alleged role in the seizure of suspects in those countries who were then flown to Egypt for interrogation. According to Dr. Georg Nolte, a law professor at the University of Munich, under international law, nations are obligated to investigate any substantiated human rights violations committed on their territory or using their airspace.

Dr. Nolte examined the case of Khaled el-Masri, a German citizen who American officials have confirmed was pulled from a bus on the Serbia-Macedonia border on Dec. 31, 2003, and held for three weeks. Then he was drugged and beaten, by his account, before being flown to Afghanistan.

The episode illustrates the circumstantial nature of the evidence on C.I.A. flights, which often coincide with the arrest and transporting of Al Qaeda suspects. No public record states how Mr. Masri was taken to Afghanistan. But flight data shows a Boeing Business Jet operated by Aero Contractors and owned by Premier Executive Transport Services, one of the C.I.A.-linked shell companies, flew from Skopje, Macedonia, to Baghdad and on to Kabul on Jan. 24, 2004, the day after Mr. Masri's passport was marked with a Macedonian exit stamp.

Mr. Masri was later released by order of Condoleezza Rice, the national security adviser at the time, after his arrest was shown to be a case of mistaken identity.

A C.I.A. spokeswoman declined to comment for this article. Representatives of Aero Contractors, Tepper Aviation and Pegasus Technologies, which operate the agency planes, said they could not discuss their clients' identities. "We've been doing business with the government for a long time, and one of the reasons is, we don't talk about it," said Robert W. Blowers, Aero's assistant manager.

A Varied Fleet

But records filed with the Federal Aviation Administration provide a detailed, if incomplete, portrait of the agency's aviation wing.

The fleet includes a World War II-era DC-3 and a sleek Gulfstream V executive jet, as well as workhorse Hercules transport planes and Spanish-built aircraft that can drop into tight airstrips. The flagship is the Boeing Business Jet, based on the 737 model, which Aero flies from Kinston, N.C., because the runway at Johnston County is too short for it.

Most of the shell companies that are the planes' nominal owners hold permits to land at American military bases worldwide, a clue to their global mission. Flight records show that at least 11 of the aircraft have landed at Camp Peary, the Virginia base where the C.I.A. operates its training facility, known as "the Farm." Several planes have also made regular trips to Guantánamo.

But the facility that turns up most often in records of the 26 planes is little Johnston County Airport, which mainly serves private pilots and a few local corporations. At one end of the 5,500-foot runway are the modest airport offices, a flight school and fuel tanks. At the other end are the hangars and offices of Aero Contractors, down a tree-lined driveway named for Charlie Day, an airplane mechanic who earned a reputation as an engine magician working on secret operations in Laos during the Vietnam War.

"To tell you the truth, I don't know what they do," said Ray Blackmon, the airport manager, noting that Aero has its own mechanics and fuel tanks, keeping nosey outsiders away. But he called the Aero workers "good neighbors," always ready to lend a tool.

Son of Air America

Aero appears to be the direct descendant of Air America, a C.I.A.-operated air "proprietary," as agency-controlled companies are called.

Just three years after the big Asian air company was closed in 1976, one of its chief pilots, Jim Rhyne, was asked to open a new air company, according to a former Aero Contractors employee whose account is supported by corporate records.

"Jim is one of the great untold stories of heroic work for the U.S. government," said Bill Leary, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Georgia who has written about the C.I.A.'s air operations. Mr. Rhyne had a prosthetic leg - he had lost one leg to enemy antiaircraft fire in Laos - that was blamed for his death in a 2001 crash while testing a friend's new plane at Johnston County Airport.

Mr. Rhyne had chosen the rural airfield in part because it was handy to Fort Bragg and many Special Forces veterans, and in part because it had no tower from which Aero's operations could be spied on, a former pilot said.

"Sometimes a plane would go in the hangar with one tail number and come out in the middle of the night with another," said the former pilot. He asked not to be identified because when he was hired, after responding to a newspaper advertisement seeking pilots for the C.I.A., he signed a secrecy agreement.

While flying for Aero in the 1980's and 1990's, the pilot said, he ferried King Hussein, Jordan's late ruler, around the United States; kept American-backed rebels like Jonas Savimbi of Angola supplied with guns and food; hopped across the jungles of Colombia to fight the drug trade; and retrieved shoulder-fired Stinger missiles and other weapons from former Soviet republics in Central Asia.

Ferrying Terrorism Suspects

Aero's planes were sent to Fort Bragg to pick up Special Forces operatives for practice runs in the Uwharrie National Forest in North Carolina, dropping supplies or attempting emergency "exfiltrations" of agents, often at night, the former pilot said. He described flying with $50,000 in cash strapped to his legs to buy fuel and working under pseudonyms that changed from job to job.

He does not recall anyone using the word "rendition." "We used to call them 'snatches,' " he said, recalling half a dozen cases. Sometimes the goal was to take a suspect from one country to another. At other times, the C.I.A. team rescued allies, including five men believed to have been marked by Muammar el-Qaddafi, the Libyan leader, for assassination.

Since 2001, the battle against terrorism has refocused and expanded the C.I.A.'s air operations. Aero's staff grew to 79 from 48 from 2001 to 2004, according to Dun and Bradstreet.

Despite the difficulty of determining the purpose of any single flight or who was aboard, the pattern of flights that coincide with known events is striking.

When Saddam Hussein was captured in Iraq the evening of Dec. 13, 2003, a Gulfstream V executive jet was already en route from Dulles Airport in Washington. It was joined in Baghdad the next day by the Boeing Business Jet, also flying from Washington.

Flights on this route were highly unusual, aviation records show. These were the first C.I.A. planes to file flight plans from Washington to Baghdad since the beginning of the war.

Flight logs show a C.I.A. plane left Dulles within 48 hours of the capture of several Al Qaeda leaders, flying to airports near the place of arrest. They included Abu Zubaida, a close aide to Osama bin Laden, captured on March 28, 2002; Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who helped plan 9/11 from Hamburg, Germany, on Sept. 10, 2002; Abd al-Rahim al-Nashri, the Qaeda operational chief in the Persian Gulf region, on Nov. 8, 2002; and Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the architect of 9/11, on March 1, 2003.

A jet also arrived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, from Dulles on May 31, 2003, after the killing in Saudi Arabia of Yusuf Bin-Salih al-Ayiri, a propagandist and former close associate of Mr. bin Laden, and the capture of Mr. Ayiri's deputy, Abdullah al-Shabrani.

Flight records sometimes lend support to otherwise unsubstantiated reports. Omar Deghayes, a Libyan-born prisoner in the American detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, has said through his lawyer that four Libyan intelligence service officers appeared in September in an interrogation cell.

Aviation records cannot corroborate his claim that the men questioned him and threatened his life. But they do show that a Gulfstream V registered to one of the C.I.A. shell companies flew from Tripoli, Libya, to Guantánamo on Sept. 8, the day before Mr. Deghayes reported first meeting the Libyan agents. The plane stopped in Jamaica and at Dulles before returning to the Johnston County Airport, flight records show.

The same Gulfstream has been linked - through witness accounts, government inquiries and news reports - to prisoner renditions from Sweden, Pakistan, Indonesia and Gambia.

Most recently, flight records show the Boeing Business Jet traveling from Sudan to Baltimore-Washington International Airport on April 17, and returning to Sudan on April 22. The trip coincides with a visit of the Sudanese intelligence chief to Washington that was reported April 30 by The Los Angeles Times.

Mysterious Companies

As the C.I.A. tries to veil such air operations, aviation regulations pose a major obstacle. Planes must have visible tail numbers, and their ownership can be easily checked by entering the number into the Federal Aviation Administration's online registry.

So, rather than purchase aircraft outright, the C.I.A. uses shell companies whose names appear unremarkable in casual checks of F.A.A. registrations.

On closer examination, however, it becomes clear that those companies appear to have no premises, only post office boxes or addresses in care of lawyers' offices. Their officers and directors, listed in state corporate databases, seem to have been invented. A search of public records for ordinary identifying information about the officers - addresses, phone numbers, house purchases, and so on - comes up with only post office boxes in Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C.

But whoever created the companies used some of the same post office box addresses and the same apparently fictitious officers for two or more of the companies. One of those seeming ghost executives, Philip P. Quincannon, for instance, is listed as an officer of Premier Executive Transport Services and Crowell Aviation Technologies, both listed to the same Massachusetts address, as well as Stevens Express Leasing in Tennessee.

No one by that name can be found in any public record other than post office boxes in Washington and Dunn Loring, Va. Those listings for Mr. Quincannon, in commercial databases, include an anomaly: His Social Security number was issued in Washington between 1993 and 1995, but his birth year is listed as 1949.

Mr. Glerum, the C.I.A. and Air America veteran, said the use of one such name on more than one company was "bad tradecraft: you shouldn't allow an element of one entity to lead to others."

He said one method used in setting up past C.I.A. proprietaries was to ask real people to volunteer to serve as officers or directors. "It was very, very easy to find patriotic Americans who were willing to help," he said.

Such an approach may have been used with Aero Contractors. William J. Rogers, 84, of Maine, said he was asked to serve on the Aero board in the 1980's because he was a former Navy pilot and past national commander of the American Legion. He knew the company did government work, but not much more, he said. "We used to meet once or twice a year," he said.

Aero's president, according to corporate records, is Norman Richardson, a North Carolina businessman who once ran a truck stop restaurant called Stormin' Norman's. Asked about his role with Aero, Mr. Richardson said only: "Most of the work we do is for the government. It's on the basis that we can't say anything about it."

Secrecy Is Difficult

Aero's much-larger ancestor, Air America, was closed down in 1976 just as the United States Senate's Church Committee issued a mixed report on the value of the C.I.A.'s use of proprietary companies. The committee questioned whether the nation would ever again be involved in covert wars. One comment appears prescient.

When one C.I.A. official told the committee that a new air proprietary should be created only if "we have a chance at keeping it secret that it is C.I.A.," Lawrence R. Houston, then agency's general counsel, objected.

In the aviation industry, said Mr. Houston, who died in 1995, "everybody knows what everybody is doing, and something new coming along is immediately the focus of a thousand eyes and prying questions."

He concluded: "I don't think you can do a real cover operation."

[original article]